There were a lot of transitions and innovations in pop and jazz singing during the 1950's. Some of these were triggered by technology-tape recording/editing, hi fi, stereo, new microphones and the long playing record (LP). Other transitions reflected innovations in arranging and instrumentation and the movement of "race music" into the mainstream via rock and roll. Leaving aside innovators in blues, R&B and rock and roll, there were two musicians who effected changes in vocal jazz and pop: Frank Sinatra and yes, Chet Baker.

Frank Sinatra and his arrangers Billy May and Nelson Riddle in "In the Wee Small Hours" (1955) and "Songs for Swingin' Lovers!" (1956) bridged a popular music gap and showed that songs could swing and still deliver an intimate romantic message.

Chet Baker's style of singing on "Chet Baker Sings" (1954) finished off what Bing Crosby started. Crosby had initiated the movement from "hot" to "cool," as he taught singers how to use the microphone. But, even though Bing's style was relatively laid back, he still used "hot" techniques like vibrato, slurs and small ornamentations to "sell" the tune. This continued to be the standard, but Baker took it a step further, either eliminating or dramatically taking down the heat of these techniques. Also, in the range and timbre of his voice, he did not sound as a man singing was supposed to. Given the negative response by fellow musicians, friends and critics, it took some guts for Baker to continue to sing.

|

| Louis Prima |

Baker's trumpet playing was not unique. It was distinguishable from but similar to the playing of others active at that time, like Jack Sheldon, Don Fagerquist, Don Joseph, Tony Fruscella and John Eardley. Of these, only Jack Sheldon also sang. His voice was better than Baker's, but his singing style ranged from cooing drollness to belting. To Sheldon, romantic meant sexy, while Chet was never so indiscreet, or overt. His sexiness was hidden below layers of romanticism and self-protection.

|

| Jimmy Scott |

Rhythmically and in note choice, Baker's singing paralleled his playing. But the fragility, tremulousness and high tenor range of his voice amplified the vulnerable quality of the music. The only voice like it belonged to (Little) Jimmy Scott, who had a hit in 1950 with Lionel Hampton's "Everybody's Somebody's Fool" and who showed up in the same year with Charlie Parker, singing "Embraceable You," but Scott sang with all of the heat that Baker eschewed.

Reading about Baker's foray into singing is like wading into a critical abattoir. Almost no one liked it-musicians, friends or critics.

There are conflicting stories about how Baker's vocals got recorded. Some say he demanded it and that owner of the Pacific jazz label Dick Bock balked. Others say that Bock wanted it and Baker resisted. Either way, it seems to be true that Baker's inexperience(or ineptitude) made for innumerable retakes, marathon sessions and a lot of audio cutting and pasting.

Two things were not subject to criticism. One was his phrasing, which rhythmically paralleled his playing. The second was his scatting note choice, which reflected the melodic gift he shows in his trumpet solos.

There was a lot of criticism about his singing out of tune. I'm pretty sensitive to people staying in tune and I don't hear the problem very much, except on some held notes-the hardest to sing in tune and beyond his vocal support system.

Critics blasted his lack of affect, saying his singing lacked emotional weight. Much was made about the girlish, non-masculine quality of his voice. Often this critique was accompanied by an analysis of Baker's life choices-drug use and callousness toward women. People want the artist's life to reflect directly the qualities they find in the art and positive and negative projections about Baker were off the charts. He was worshipped and reviled. Some thought he sang (and looked) like an angel. Others saw him nod out or act like a cad and heard that in the music.

What I think made critics most uncomfortable is that Baker didn't sing like a man. I've heard people ask, when they heard Baker sing, whether that was a man or a woman. One can only imagine how many such comments were passed in the day. For most of its history, jazz has been a macho culture. Sexual ambiguity or gay-ness were subjects of derision. Chet was heterosexual, but for him to sing the way he did was almost to "come out." Of course, Baker wasn't consciously making a political-sexual point. When he responded to interviewers who challenged his masculinity, he made certain to reaffirm that he liked girls, not "fellers."

Moving from being just a trumpet player to becoming a jazz vocalist/leading man, seeing the response it got from critics and especially from fellow musicians, cannot have been easy. Baker may or may not have been using heavy drugs before "Chet Baker Sings," but there's no doubt that he became more deeply enmeshed in heroin and speed during this period. It's not a big stretch to think that drugs and the incredibly strong response by women to his singing helped Baker weather the brickbats and continue to sing.

It's appropriate that his most famous vocal tune is "My Funny Valentine." In this Rodgers and Hart tune, we have a psychic match between performer and song. This is a song that spells out the imperfections of the lover ("is your figure less than greek, is your mouth a little weak, when you open it to speak are you smart"). Look at the title itself-my "funny" valentine; not that the lover is funny/humorous, but funny as in-how did this happen-how did I end up with someone like you. This is love as mystery, song as mystery, sung by a musician whose life was lived publicly, but who was a mystery. Yes, we know the biographical facts of Baker's life, but the inner life was shrouded in layers of romanticism and self-protection.

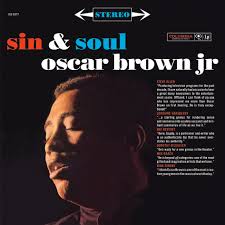

It's difficult to show the influence Baker had, as he didn't overtly inspire a generation of male singers. Most tenor-range jazz vocalists remained more beholden to older approaches. Jimmy Scott, Tony Bennett, Johnny Mathis, Mose Allison, Oscar Brown, Jr., Mark Murphy, Jackie Paris and Sammy Davis, Jr. were all much "hotter" singers.

But I contend that Chet Baker changed the "field" and in so doing influenced these singers. He brought the ethos of cool to a kind of climax by moving into territory that had once belonged only to female vocalists and opened up the emotional space to show vulnerability; a space that male singers had previously shied away from and which they were now more likely to inhabit.

Ironic that Chet Baker, who created such distance between himself from others was able to transmute this distance into a kind of intimacy that had rarely, if ever, been expressed in the pop-jazz male voice.